Restoration

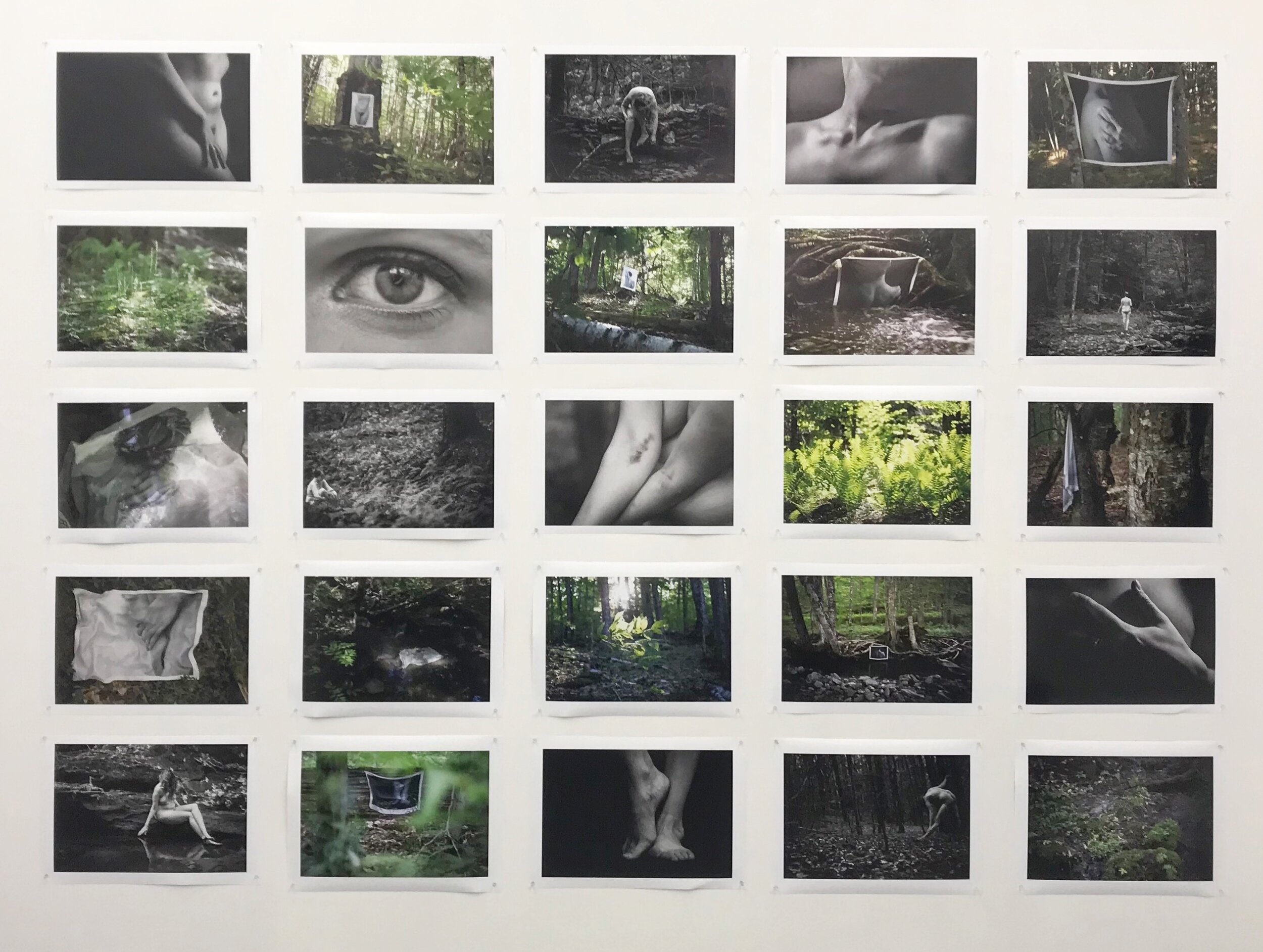

During the summer of 2018, while partially blind, I created a durational work of art in the forest surrounding my childhood home in South Strafford, Vermont. At the beginning of summer, I placed seventeen black and white fabric prints of my body in the forest, and watched over the next few months as they slowly disintegrated. I feel most comfortable in this place: barefoot, muddy, scratched and raw. I know the way that the rocks shift beneath my weight, the strength of the tree roots I use to climb. I know which plants are poisonous and under what conditions. I know the feeling of the air before a storm. Being disabled usually negatively affects the way that I negotiate space, but in this place where I first learned how to walk and how to see, my body is perfect. As the summer ended, I retrieved my photographs from the trees and streams where they had become imbedded. I had watched them as they changed from pristine blacks and whites to faded browns and greys. Edges frayed and coated in pine sap, the work finally felt whole.

To me these works are about the restoration of body and place. My body can never be restored, only conserved. To quote Eli Clare: “[Cure] grounds itself in an original state of being, relying on the belief that what existed before is superior to what exists currently…but for some of us, even if we accept disability as damage to individual body-minds, these tenets quickly become tangled, because an original non-disabled state of being doesn’t exist.” These photographs represent more than their physical forms. They are wind-battered and torn, but they are still me.